Burnout or Compassion Fatigue? What’s the Difference, How Advisors Can Cope, and Strategies for Creating Resilience

Share this

How are you doing? No, really—how are you?

Not great? That’s okay.

Tired? Frustrated? Sad? Just plain awful? That’s okay, too.

You’re not alone. Now, more than ever, we are all trying to make sense of the world and our places within it. We’ve all been plunged headfirst into a VUCA existence. VUCA, a US Army War College acronym which stands for volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, has recently become a catchy managerial phrase to describe a state of flux or change in an organization which creates a destabilizing effect, but the term is equally applicable to the upset in most people’s personal and professional lives surrounding the outbreak of COVID-19.

One of the effects of this uncertainty has been directly applicable to advisors. According to a Nationwide Retirement Institute survey of more than 2,000 adults age 18 and over, roughly 1 in 4 Americans (24% of all respondents and 26% of investors) engaged the help of a financial advisor for the first time because of the coronavirus crisis.

While this is good news overall, the outcome of this wave of people requiring assistance creates new challenges for advisors facing the pressure to respond.

With the increase in pressure, you may be feeling a bit detached. You also may have noticed your patience is much shorter and you’re quicker to respond sharply to team members, family, or friends who get on your nerves. Or maybe you're finding that ordinary tasks, like responding to email, seem to take so much more energy than normal. You may even be wondering if you’re suffering from burnout.

Symptoms of burnout can frequently include feelings of fatigue, frustration, negativity, withdrawal, anger, and increasingly negative reactions toward others. In general, burnout tends to accumulate slowly over time, building in pressure until you hit a point of critical mass where it feels impossible to continue.

What you may actually be suffering from is something called compassion fatigue.

Compassion fatigue often mimics burnout but can have a much quicker onset. Thankfully, compassion fatigue can also have a significantly faster recovery time if it’s caught early.

Recognizing the Signs of Compassion Fatigue

So, what is compassion fatigue? While generally associated with healthcare and mental health professionals, compassion fatigue can affect anyone who works with people who have suffered traumatic events or who are in a state of crisis. Compassion fatigue has been defined and researched by psychologist Charles Figley, who describes it as “a state of exhaustion and dysfunction, biologically, physiologically and emotionally, as a result of prolonged exposure to compassion stress.”

Advisors are particularly vulnerable to compassion fatigue by the empathetic nature of their work. Helping clients adapt to difficult life changes such as chronic or terminal illnesses, job loss, divorce, aging parents, or economic downturn requires substantial emotional energy and can be incredibly draining. You may also be leading a team who are also looking to you for support and guidance as they struggle to find their own balance during difficult times.

How do you know if what you are feeling is compassion fatigue? Some commons symptoms of compassion fatigue include:

- Chronic physical and emotional exhaustion

- Irritability

- Feelings of self-contempt

- Difficulty sleeping

- Weight loss

- Headaches

- Poor job satisfaction

- Feeling burdened by the suffering of others

- Isolating yourself

- Loss of pleasure in life

- Difficulty concentrating

- Bottling up your emotions

- Increased nightmares

- Feelings of hopelessness or powerlessness

- Lack of attention to self-care

- Denial

If you are still unsure, you can self-assess where you are on the compassion satisfaction/fatigue continuum using the Professional Quality of Life (PROQOL) questionnaire, which was developed by Dr. Beth Hundall Stamm, one of the world's leading experts on compassion fatigue.

How to Cope with Compassion Fatigue

What happens next? Building a recovery plan for compassion fatigue is a very personal process. Not all of the tips or techniques that are helpful to one person will be useful to another. Finding your personal recovery path will require some trial and error to see what works best for you and provides the most benefit for your situation. I’ll introduce you to a few different techniques and tips that you can use to develop a plan that works well for you.

The first step is taking a minute to tap into your self-awareness. Let’s do a quick self-check-in. How is your energy? Your mood? Your motivation? Give yourself a score: on a scale of 1 (“I need a nap immediately/Why does thinking hurt?”) to 6 (“I could run a marathon right now/I feel invincible!”). Acknowledge where you are at right now and tell yourself that it’s okay, regardless of whether you’re feeling like a tired “2” or an ambitious “9.” Being willing to accept your current capacity is the first step in moving away from denial and guilt over not being your most productive and compassionate self at every moment of every day and giving yourself permission to accept the ebb and flow of your energy and stress levels.

If you continue to check-in with yourself periodically, you’ll notice that your ratings will likely change throughout the week or even throughout the course of a day. In this case, change is a good thing! Know that even if you are feeling like a “3” right now, you may feel like a “6” tomorrow. I’d recommend keeping a journal or even just making a quick note on your calendar whenever you conduct your self check-in so that you can see if patterns emerge over time. Are you typically feeling better and more energetic early in the day or later in the afternoon? Are Mondays lower or higher motivation days than Fridays?

If you see trends emerging, use that data to guide how you structure your schedule. If Tuesday mornings are frequently peak energy periods, prioritize using that time for activities that require additional capacity, the type of work you choose to perform depends on your personality and preferences. For example, introverts may need the extra boost for client meetings or other interactions, but extroverts may find quiet, focused work requires more stamina. Another tip: if you spend a significant amount of your time in virtual meetings, try to schedule shorter meetings at more frequent intervals, which has been demonstrated to reduce “Zoom fatigue” or the additional mental strain associated with virtual video interactions.

If you manage other people, this is an activity you can introduce to your team and encourage them to share their ratings if they feel comfortable. Knowing how your team is feeling is an especially valuable connection point if your team is working remotely, and you may not be able to pick up on body language or other cues that you would have from in-person interactions.

Now that you have a better understanding of your own energy levels, you can adapt more easily to periods of low energy or mood. One of the keys to balancing your energy and increasing your capacity, especially when you’re not feeling your best, is by reducing cognitive overload. Your brain is not well-adapted to extended periods of heightened attention covering a broad range of concerns or many varied pieces of information. Under significant stress, your brain will try to narrow your focus to the most imminent threat to exclusion of other input it deems nonessential. The reticular activating system (RAS) is one section of the brain that has a significant impact on this process.

The RAS is a segment of the brain located just above the spinal cord that interfaces between the sensory systems and the conscious mind. The RAS’s function helps improve cognitive performance under “noisy” conditions when irrelevant stimuli can impair performance. During periods of intense pressure or mental or emotional strain, however, the RAS can make it difficult to mentally distance yourself from your stressors or apply your focus to work or daily tasks.

Even though you are fundamentally wired to be distracted from what your brain considers low-priority processes (however much you may disagree with that assessment), you can improve your response through calculated action. Psychological distancing is one such tool that allows you to create emotional space between yourself and your stressors which will allow you to take the 30,000-foot view of the situation and decrease your brain’s instinctive fight or flight response.

Psychological distancing has its roots in Stoic philosophy. Marcus Aurelius was noted as saying:

“You can rid yourself of many useless things among those that disturb you, for they lie entirely in your imagination; and you will then gain for yourself ample space by comprehending the whole universe in your mind, and by contemplating the eternity of time, and observing the rapid change of every part of everything, how short is the time from birth to dissolution, and the illimitable time before birth as well as the equally boundless time after dissolution.”

A spatial distancing visualization exercise that helps move your mindset to a broader view would be to picture yourself from a third-person perspective and gradually zoom out your mental picture to encompass images of the issues that are most pressing to you. Let your mind continue to zoom out until you’re looking down through the clouds at the increasingly distant images below. Then, try zooming out even further until you’re seeing the earth down below. Alternatively, you can use a temporal distancing visualization to picture your obstacles as finite periods on the timeline of your life and then slowly zoom out to encompass the entire timeline of history. You can find many additional resources available online to facilitate a practice of meditation and continue to increase your mindfulness and self-awareness over time. XYPN Director of Member Services, Maddy Roche, has been offering morning meditations for the XYPN community. (If you’re an XYPN member, you can access the recordings here.)

How to Build Resilience

Once you’ve reduced some of the unconscious pressure to hyper-focus, you should have a corresponding decrease in your perception of being overwhelmed mentally and emotionally. At this point, turning your attention to building resilience will help establish a reservoir of resources that you can continue to draw upon as needed. Psychologists define resilience as the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress. You can think of resilience as a protective shield that buffers you from external hardships. Like a muscle, resilience can be built and improved with practice. The more that you develop your own resilience, the less likely you are to be damagingly affected when confronted with a crisis or stressor. Some factors that affect your personal level of resilience include your mindset, self-confidence, routine, and social support.

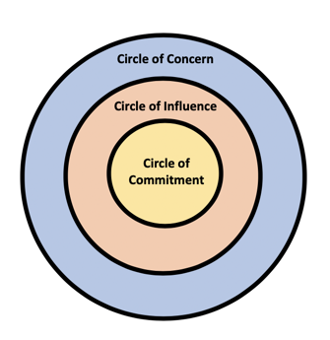

Starting with your mindset, a good way to build on the “zoom out” visualization exercise is to reframe your viewpoint around your concerns. Stephen Covey introduced a useful tool known as the Circle of Influence in his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People to illustrate the concept. The tool is an image of two or three concentric circles, wherein the largest outer circle represents your circle of concern. The circle of concern contains all of the issues that concern you in any way, everything from your personal finances to the national debt. Inside that circle is a smaller circle that includes a subset of the issues in your circle of concern, but it is limited to the issues in which you have the ability to directly influence, your circle of influence.

For example, you can influence your concern about your personal finances (circle of influence), but you can’t necessarily influence your concern about the national debt (circle of concern). By focusing on issues within your circle of influence, you can release the pressure on yourself to worry about situations and issues in which you have no control over, and you will increase your effectiveness in impacting issues within your circle of influence. In some illustrations, there is a third circle inside the circle of influence that represents your circle of commitment that represents the issues on which you have made a conscious decision to spend your time and energy.

The other half of the mindset equation is related to outlook. In the book Good to Great, Jim Collins shares what has become known as the “Stockdale Paradox,” the story of how Admiral Jim Stockdale survived seven years of torture in a prison camp, largely due to his firm belief that he would survive, and in his own words, “I would also prevail by turning it into the defining event of my life that would make me a stronger and better person.”

That is not to say that looking on the bright side will cause all of your problems to dissipate. Conversely, when asked who among the group did not fare as well, Admiral Stockdale replied:

“The optimists. Yes. They were the ones who always said, ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ Christmas would come and it would go. And there would be another Christmas. And they died of a broken heart. This is what I learned from those years in the prison camp, where all those constraints just were oppressive. You must never ever ever confuse, on the one hand, the need for absolute, unwavering faith that you can prevail despite those constraints with, on the other hand, the need for the discipline to begin by confronting the brutal facts, whatever they are.”

The key to creating a resilience-building outlook is all about balance. As the Stockdale Paradox teaches, the ideal outlook requires planning for positive outcomes, while still remaining competent and grounded. Viewing the obstacles in your path as challenges for personal growth accomplishes both objectives by acknowledging the difficulties you face but reframing them as something that you can overcome and that you will be positively impacted by the process of conquering those challenges. Take strategic action to ensure a positive outcome: start by envisioning yourself succeeding. What does success look like? What is one positive step that you can take now to move closer to that goal?

The next factor in resilience is self-confidence. During times of adversity, self-confidence can feel like a very difficult factor to influence, but Jeanie Daniel Duck said it best with this statement: “Confidence is success remembered.” Often, looking back over past wins can bring about a confidence boost when you most need it. Keeping a “brag sheet” or win journal is a great way to compile a source of encouragement for the tough times.

If you don’t have a win journal to look back on, another activity that can be beneficial is to think back to a time when you felt extremely successful. What are one or two words that describe you at your best? Write those words down and post them somewhere very visible where you can see them when you need to reconnect with the strong, smart, funny, creative, wise, (or whatever the case may be) person who you are and who is capable of sharing those strengths with the people whose lives you touch.

Following mindset on the list of factors is routine. Many times, stress and frustrations in life are accompanied by a substantial dose of disruption. Disruption heavily contributes to feeling a loss of control and an uncomfortable level of unfamiliarity, both of which are detrimental to finding a sense of stability and perspective when faced with difficulties. Finding and consistently adhering to a disciplined and supportive routine can significantly reduce the impact of outside disruptions. Routines don’t need to be extensive to be effective, either. Even just choosing one or two activities that you can commit to accomplishing can provide a much greater sense of balance and security. Sometimes the term “self-care” can be a bit overused, but this is your opportunity to prioritize meeting the needs that contribute to your individual wellbeing. Struggling to come up with a routine? Try brainstorming ideas by remembering a really good day that you’ve had. What did you do? What activities set you up for success? It’s ok to start small! Was it skipping that second cup of coffee? Squeezing in an evening workout? Preparing your lunch the night before? Journaling? Maybe the key for you is having quiet time for reflection; how about trying a 10-minute morning meditation? Pick one activity and try incorporating it into your routine for a week? Does it support you having a higher rating in your self-check-in? If so, keep it up! If not, pick another activity and give it a try. Keep tweaking your routine until you find something that works for you and your schedule.

Part of establishing your routine involves setting boundaries around your time and attention. It’s impossible to stick to a plan if you aren’t able to protect yourself from interruptions. This can be especially relevant if you lead a team. It’s an easy trap to fall into to feel like being a leader requires you to be available at all times. It does not. A big part of the compassion fatigue cycle can develop from the pressure to be constantly available, which, over time, will often lead to feelings of resentment and frustration if you no longer have control over your schedule or the ability to accomplish your personal objectives. As flight attendants like to remind us: you need to put on your oxygen mask first, before assisting others! The same concept applies to creating boundaries around your routine. You can be supportive without becoming self-sacrificing. Setting clear guidelines around when you are available for questions or when you can be expected to respond to emails or messages can also go a long way towards modeling good boundary-setting behavior for your team members and can help them set boundaries with their clients.

The final aspect of resilience is social support. The American Psychological Association wrote in its resilience report: “Many studies show that the primary factor in resilience is having caring and supportive relationships within and outside the family. Relationships that create love and trust, provide role models, and offer encouragement and reassurance, help bolster a person’s resilience.” The primary factor in resilience. Wow!

For many of us, our main sources of social support come from family or friends, but other forms of social support can have considerable value, especially when facing work-related compassion fatigue. Never discount the value of an impartial, neutral listener! Many people struggle with guilt over the thought of burdening their closest relationships with their own problems, and this feeling can be an especially daunting burden to professionals who have made it their mission to help support others with their work. Reaching out to a therapist is not a cause for shame, and it most definitely is not a sign of failure. Finding someone who you trust and who will treat YOU with compassion may be the single most important decision you make to recover from compassion fatigue. Other supportive relationships and connections which can contribute to increased resilience could include professional mentors, other entrepreneurs, or industry-specific support groups or communities (hmm… sounds familiar…. XYPN, perhaps?). Sharing your successes and lessons learned with other professionals is also a wonderful way to boost your self-compassion by embracing our common humanity with others who have similar experiences.

While feelings of compassion fatigue can seem overwhelming and may even appear insurmountable at times, you are not alone. Understanding the complex emotions and symptoms that you are struggling with is the first step to moving towards recovery.

Along with the tools and techniques above, I’ll leave you with one additional piece of advice: be kind to yourself. In the battle against compassion fatigue, self-compassion is an essential weapon.

“If your compassion does not include yourself, it is incomplete.” –Jack Kornfield

About the Author

As the Talent Development Manager for XY Planning Network, Ashley champions the company’s culture and values by building and executing training and development strategies focused on motivating, engaging, and educating XY’s committed and high performing team. She is a self-professed “geek” with a love of all things related to learning and development. Outside of work, Ashley is frequently spotted petting strangers’ dogs, paddle boarding, backcountry skiing, reading science fiction novels, and photographing pretty much everything around beautiful Bozeman, Montana.

Share this

- Advisor Blog (698)

- Financial Advisors (222)

- Growing an RIA (121)

- Digital Marketing (87)

- Marketing (84)

- Community (81)

- Business Development (78)

- Start an RIA (76)

- Coaching (72)

- Running an RIA (71)

- Compliance (69)

- Client Acquisition (65)

- Technology (65)

- Entrepreneurship (61)

- XYPN LIVE (60)

- Sales (49)

- Practice Management (44)

- Client Engagement (41)

- Bookkeeping (40)

- Investment Management (40)

- XYPN Books (38)

- Fee-only advisor (37)

- Scaling an RIA (33)

- Employee Engagement (31)

- Lifestyle, Family, & Personal Finance (31)

- Financial Education & Resources (27)

- Client Services (26)

- Journey Makers (22)

- Market Trends (21)

- Process (14)

- Niche (11)

- SEO (9)

- Career Change (8)

- Partnership (7)

- Transitioning Your Business (7)

- Sapphire (4)

- Transitioning To Fee-Only (4)

- Social Media (3)

- Transitioning Clients (3)

- Emerald (2)

- Persona (2)

- RIA (2)

- Onboarding (1)

Subscribe by email

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

Getting Involved in the Financial Planning Community - What Would Arlene Say?

Mar 15, 2018

12 min read

Why Self-Care and Family-Care Are Key to Business Success - What Would Arlene Say?

Oct 5, 2017

6 min read